Who Became President in 1868 and Again in 1872?

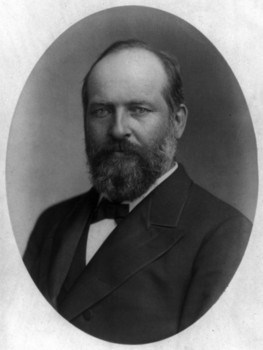

Library of Congress

The 43rd Congress

1872 was over again a presidential ballot twelvemonth, with Grant running for a second term confronting Horace Greeley, the candidate for a rebellious splinter grouping of "liberal Republicans" and the Democrats. "In my interior view of the case," said Garfield, "I would say Grant was not fit to exist nominated and Greeley is non fit to be elected." But Garfield'due south ain election prospects improved with the redistricting after the 1870 census. The nineteenth district was redrawn, removing Mahoning County and adding Lake County, freeing Garfield from the "Iron men" of the Mahoning Valley, and adding another solidly Republican voting bloc. His nomination was unopposed, and his election was 19,189 votes to viii,254.

Library of Congress

The 44th Congress

Garfield faced his stiffest challenge to re-election in 1874. Grant's second term was consumed by scandal and mired in depression. Voters were by and large in a foul, "throw-the-bums-out" mood. And in the nineteenth district local Republican conventions were passing resolutions condemning Garfield'southward association with the Credit Mobilier scandal and the congressional "salary grab." At least one local political party meeting passed a resolution demanding Garfield's immediate resignation.

For the start time, Garfield and his political friends in the district knew that they were in a real fight. In January, Garfield told Harmon Austin, his nigh of import local counselor, that he would "abide by all your engagements, and will send y'all the means to pay all expenses. There are political friends hither [in Washington] that will aid in raising the necessary funds if I am no able to carry the load alone."

A 3rd scandal involving a contract for paving the streets of Washington, D.C. added to the tense temper, simply the issue that well-nigh angry the voters of the nineteeth district was the "salary grab." As a part of the almanac appropriation pecker, congress had voted itself a $2,500 heighten, retroactive to the beginning of the 43rd Congress. This, when the legislature was cut programs beyond the government, was simple for voters to understand and vocally oppose. As chairman of the appropriations committee in the House, Garfield was seen as personally responsible for the passage of the "salary grab" even though he had opposed it in commission and on the floor of the Business firm.

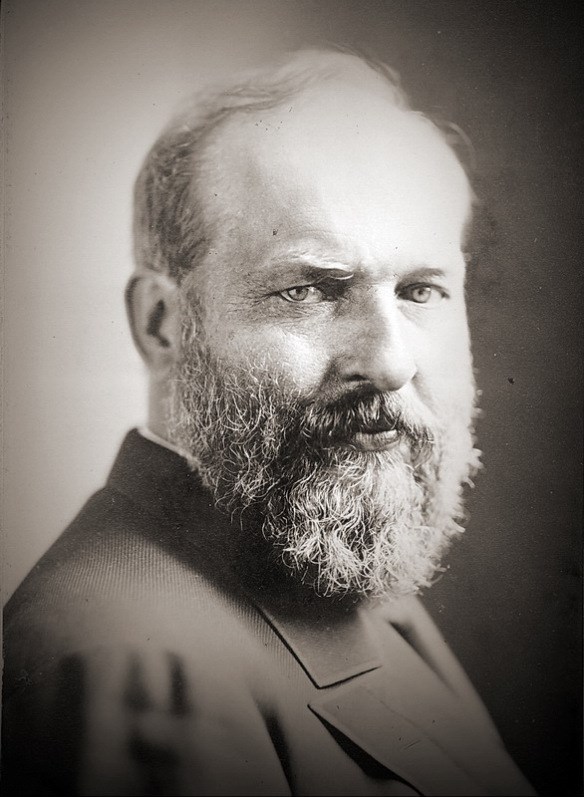

Library of Congress

So Garfield returned to his district and campaigned for delegates to the local nominating conventions, explaining his positions mostly in small meetings and through his friends. In August he wrote in his diary: "The District is very thoroughly aroused and we shall have large principal meetings. My enemies are bitter and noisy, my friends more active than ever before and full of fight." Harmon Austin had developed an impressive political motorcar to encounter challenge, and when voters met at the township level to choose delegates to the district convention, the Garfield forces showed up. The Congressman netted ii-thirds of the local delegates, and by the time the district convention met the opposition had collapsed.

But the disaffected Republicans didn't surrender; instead they named an independent candidate, H. R. Hurlburt, to challenge Garfield and the Democratic candidate Daniel B. Woods, who had run confronting Garfield in his showtime campaign twelve years earlier. In a calendar month of fierce political fighting, Garfield attempted to answer every question and every challenge. "I let these gentlemen know that during this entrada it was to exist blow for blow and those who struck must expect a blow in return." In refuting the queries of a questioner named Tuttle, Garfield said, "I dubiousness if he knew when I left him whether he was hash or jelly."

On ballot day the outcome was Garfield 12,591, Hurlburt three,427 and Woods six,245. Garfield retained his seat, but a nationwide "blue moving ridge" meant that his party lost its majority in the House. For the rest of his career in Congress, Garfield would serve in the minority.

The 45th Congress

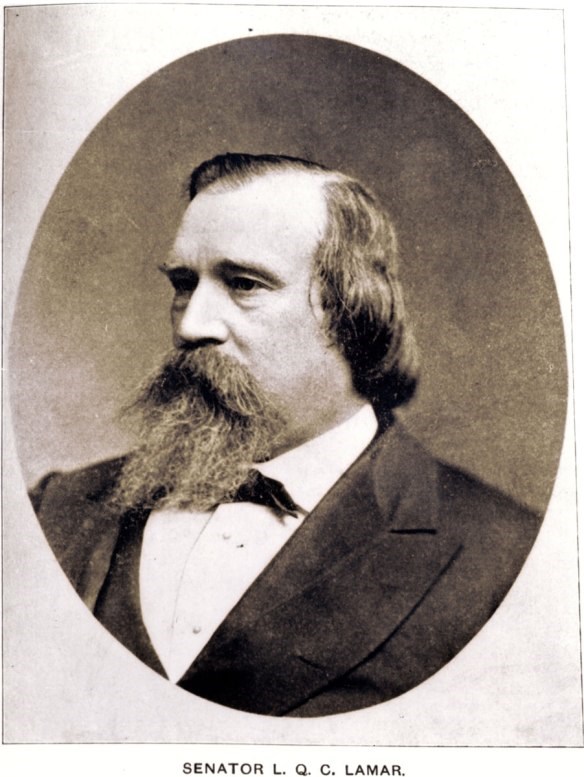

Information technology was his position as leader of the minority that gave Garfield his springboard to the 1876 ballot. At the cease of the congressional session that spring, Autonomous Congressman Fifty.Q.C. Lamar of Mississippi, whom Garfield respected as among the ablest Democrats in the House, delivered a carefully written and polished defense of the Autonomous Party. It was immediately seen equally the opening argument for the upcoming presidential campaign, when the Democrats saw their first real opportunity to win the White Firm since the Civil State of war. The adjacent day, Garfield, as the Republican leader in the Business firm, answered with a nearly extemporaneous response, arguing that the Democrats could not be trusted to manage the regime. His speech communication was immediately praised past Republicans and Republican newspapers, and was reprinted for circulation everywhere.

Library of Congress

The 46th Congress

In 1878, the Ohio legislature, controlled by Democrats, redrew the state'southward congressional districts for partisan reward. Portage County, Garfield'south abode for virtually of his life, and his original political base, was moved to another, more than Democratic, district. Mahoning Canton, with the "Iron men" who so often disagreed with and criticized Garfield, was returned to the nineteenth.

Garfield was unanimously re-nominated by the Republicans, simply he was challenge not simply by a Democratic candidate, but also by an emerging Greenback party, whose candidate, Thou, Northward. Tuttle, had been one of Garfield's loudest critics back in 1874. The main issue in the district, and across the country, was greenback currency or specie resumption. It was an issue that never seemed to exist resolved, but one where Garfield's hard coin position was well know.

Garfield 17,166 Hubbard 7,553 Tuttle 3,148

The 46th Congress was the last to which James Garfield was elected. During the term of that Congress he would be selected past the Ohio legislature to serve in the U.s.a. Senate, and later that yr (1880) was nominated as the Republican presidential candidate. During the nearly eighteen years Garfield served in Congress, he faced a number of issues and a variety of challenges. It is clear in looking over his congressional campaigns that he enjoyed the rough-and-tumble of campaigning, even though he often protested otherwise. Ii things remained constant in Garfield's political philosophy—his insistence on independence of judgment, and his loyalty to the Republican Political party.

Written by Joan Kapsch, Park Guide, James A. Garfield National Historic Site, November 2018 for the Garfield Observer.

Source: https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/james-garfield-congressman-part-ii.htm

0 Response to "Who Became President in 1868 and Again in 1872?"

Post a Comment